- Home

- Asha Lemmie

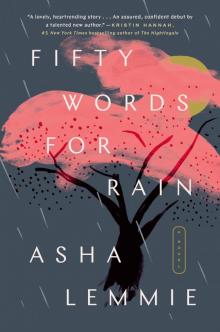

Fifty Words for Rain Page 2

Fifty Words for Rain Read online

Page 2

But her favorite thing, by far, was the half-moon-shaped window above her bed that overlooked the gardens. When she stood on the bed (which she was not supposed to do but she did anyway), she could see the fenced-in yard with its green grass and its overgrown, ancient peach trees. She could see the man-made pond with the koi fish swimming in it and splashing about. She could see the faint outline of neighboring rooftops. As far as Nori was concerned, she could see the entire world.

How many times had she spent all night with her head pressed against the cool, damp glass? Certainly very many, and she considered herself quite fortunate that she had never been caught. That would have been a guaranteed beating.

She had not been allowed to leave the house since the day she arrived. And it was not a terrible sacrifice, not really, because she had rarely been allowed to leave the apartment she’d shared with her mother either.

Still, there were rules, many rules, for living in this house.

The cardinal rule was simple: stay out of sight unless summoned. Remain in the attic. Make no sound. Food was brought to her at set intervals three times a day; Akiko would take her downstairs to the bathroom. During the midday trip, Nori would have her bath.

Three times a week, an old man with a hunched back and failing eyesight would come to her attic and teach her reading, writing, numbers, and history. This one did not feel like a rule—Nori liked lessons. In fact, she was quite gifted at them. She was always asking Saotome-sensei to bring her new books. Last week, he’d brought her a book in English called Oliver Twist. She could not read a single word of it, but she had resolved to learn. It was such a pretty book, leather-bound and glistening.

And so those were the rules. They weren’t too much to ask, she didn’t think. She didn’t understand them, but then, she didn’t try.

Don’t think.

Nori crept onto her small four-poster bed and pressed her face into the coolness of her pillow. It distracted her from her skin’s persistent tingling. The instinctual desire to escape from pain soon lulled her into a listless sleep.

She had the same dream as always.

She was chasing the blue car as it drove away, calling out for her mother, but could never catch it.

* * *

As long as she could remember, Nori’s limbs had been prone to disobedience. They would begin to shake, randomly and uncontrollably, at the slightest hint of trouble. She would have to wrap her arms around her body and squeeze as tightly as she could in order for the trembling to subside.

And so when Akiko informed her that her grandmother would be paying her a visit today, Nori felt her body go weak. She slunk into one of her small wooden dining chairs, no longer trusting her legs to support her.

“Obaasama is coming?”

“Yes, little madam.”

Her grandmother normally came once a month, sometimes twice, to inspect Nori’s living conditions and personal growth.

It seemed that no matter what she did, her grandmother was never pleased. The old woman had impeccable standards and her keen gray eyes never missed a beat. It filled Nori with as much exhilaration as it did dread.

To please her grandmother was a feat that she longed to accomplish. In her mind, it was the most noble of quests.

Nori swept her eyes around her room, suddenly painfully aware of how messy things were. There was a corner of faint yellow bedclothes sticking out. There was a speck of dust on the kerosene lamp on the nightstand. The wood burning in the stove was popping and cracking, a sound that some would surely find irritating.

Wordlessly, the maid began to move about the room, tidying and putting things into their proper place. Akiko too was used to the demands of the lady of the house. She had been working here since she herself was a mere child.

Of course, that meant that Akiko had known Nori’s mother. This was a curious dynamic between them: Nori always wanting to ask and Akiko always wanting to tell, but both too obedient to do either.

“What shall I wear?” Nori rasped, hating the sudden waver in her voice. “What do you think?”

Nori immediately began to rack her brains. She had a polka-dot navy blue dress, with short sleeves and a lace collar. She had a green kimono with a pale pink sash. She had a bright yellow yukata, which she could wear now that it was summer. And she had a dark purple kimono. That was all.

She began to gnaw gently on the skin inside her left cheek. “The black one,” she said resolutely, answering her own question. Akiko went to the closet and laid it out on the bed.

Nori arrived at this conclusion relatively easily. In contrast to the dark hues of the garment, her skin would appear lighter. Akiko brought the kimono over and began to dress her, while her mind began to wander to other places.

She ran an unsteady hand through her hair. God, she hated her hair. It was thick and boisterous, stubbornly curly despite her daily efforts to tame it with a brush. It was also a peculiar shade of dark brown that Nori likened to the bark of an oak tree. She could not get it to fall straight and free around her shoulders, as her mother’s and grandmother’s did.

However, if she brushed the hair hard against her scalp, it would flatten enough that she could wind it into a long braid that she would tie neatly behind her head. It fell nearly to her waist, and she bound the end of it with a brightly colored ribbon. If she did it that way, it looked almost normal.

She was wearing the red ribbon today, one of her twelve. It was her favorite one, as she thought it brought out the brightness in her champagne-colored gaze. The one thing she did like about her face was her eyes—even her grandmother remarked once, in passing, that they were “quite interesting.”

They were gently almond-shaped, just as they should be. At least there, she did not stand out so much.

Once Nori had been dressed, Akiko took her leave.

Nori made her way to the center of the room and stood, bone straight, waiting. She willed herself not to fidget. She folded her hands neatly in front of her chest, eyeing the skin with mild contempt. It was improving. Two years of the baths and she was starting to see a change. She estimated that in another two years it would be fair enough that she could leave the attic.

Unlike her grandmother, who visited occasionally, her grandfather did his absolute best to avoid her entirely, and besides, as the Emperor’s advisor he was in Tokyo most of the time anyway. On those very rare occasions when they did cross paths, he looked at her with eyes as hard as coal. It always left her feeling cold. She sometimes asked Akiko about him. Her face would flatten and she’d say simply, “He is a very important man, a very powerful man.” And then she would hurriedly change the subject.

Curious as she was, Nori was not fool enough to broach the subject with her grandmother. She remembered her mother’s advice well, and though she still did not understand it much, it had proved to be quite useful. Of course, it did nothing to tell her where her mother was or when she was coming back. Nori tried not to think about these things.

The sound of footsteps alerted Nori to her grandmother’s arrival. Rather than looking up, she lowered her eyes to the floor and dropped into a low bow.

The woman before her was silent for a moment. Then she sighed. “Noriko.”

This was an indication that permission to rise had been granted. Nori straightened slowly, making sure to keep her eyes lowered respectfully.

The old woman walked briskly over to where Nori was standing and, in one deft motion, reached out and lifted her chin with a slender finger.

Nori looked at her grandmother’s face. Traces of beauty were still present despite the marks of time. Fine wrinkles decorated the smooth skin, a shade of yellow so faint it was nearly eggshell white. Her grandmother’s features were those of a classic belle: long neck, small hands, and tapered fingers. Dark hair, streaked with more white every passing year, that fell in a perfectly straight sheen well below the waist. Delicat

e nose and poignant, finely shaped eyes colored the striking shade of Kamiza gray-black that reminded Nori, with a none-too-gentle pang, of her mother.

And of course there was the swan-like elegance and grace that seemed to evade her so frustratingly, possessed by both generations that had come before. It was beautiful and maddening to behold.

“Konnichiwa, Obaasama,” Nori said, trying not to wither under the intensity of her grandmother’s glare. “God grant you well-being and joy.”

Yuko nodded, as if checking off a mental checklist. She backed away slightly, and Nori let out a barely audible sigh of relief. The old woman did a cursory sweep of the attic and then nodded once more.

Nori pulled out one of the chairs at her dining table in anticipation. But her grandmother made no move to sit.

“You have grown some, I think.”

She nearly jumped out of her skin. This was a question she was not prepared for.

“A little, Obaasama.”

“How old are you now?”

Nori bit her lip, willing her emotions to retreat back into their cavern, somewhere at the bottom of her stomach.

“Ten, Grandmother.”

“Ten. Have you bled yet?”

Nori felt panic seize her. Bled? She was supposed to bleed?

“I . . . I am sorry. I do not understand.”

Rather than reacting with disdain or fury, as Nori might expect, her grandmother only nodded yet again. These were all answers she expected.

“How are your studies?”

At this, Nori brightened instantly. For a moment, she forgot herself.

“Oh, they are wonderful. Saotome-sensei is a very good teacher. And he says I shall have more books when I can read a little better. I already have two new books and they are in English. He says that I have a natural facility for—”

Yuko turned a cold stare in Nori’s direction, and it cut her off at the knees. She ceased speaking at once, tasting bile when she closed her mouth.

It is good for a woman to learn silence.

Nori lowered her head. She eyed the faded wooden floor beneath her feet, wishing she could become one with it. To her absolute horror, she felt the beginnings of tears stir behind her eyes. She blinked in rapid succession to push them back.

After what seemed like an eon of silence, her grandmother spoke.

“How much do you weigh?”

Nori knew the answer to this query at once, thank God. She was weighed every day before her bath.

“Thirty-nine pounds, Grandmother.”

Her grandmother nodded again. “Your hair is growing out nicely. Your complexion is improved, slightly. I have sent for a new product. I expect it will arrive presently.”

“Thank you, Grandmother.”

“You could be pretty one day, Noriko. Quite pretty.”

“Thank you.”

Once, this statement would have filled Nori with joy, given her hope, given her a sense of a future outside of this attic. The future was something that racked her with constant anxiety. She had no knowledge of it or plan for it. And one day it would be there, staring her dead in the eye, and she would have nothing to say to it. So when her grandmother spoke like this, it should be cause for happiness.

But though the words still filled her with a sense of optimism, she now knew what followed this promise of tomorrow.

Wordlessly, her grandmother produced a wooden kitchen spoon from the folds of her sleeves. Despite the familiarity of this routine, Nori felt herself begin to shake almost to the point of convulsing. Once again, she had failed. She was one step further away from leaving this attic and joining the civilized world. She wasn’t ready yet. She might never be ready.

Yuko licked her thin lips. “A girl must have discipline. You are learning, this is true. I hear reports on you from Akiko-san and your teacher. But you are still too impertinent. Too bold in your ways. Like your whore mother.”

Nori clenched her hands around the wooden chair she was still holding on to. Without being prompted, she bent over.

Her grandmother continued. “You are good at your studies, but this is not so important. You lack poise and grace. I can hear your footsteps shaking the house, like a zou. We are royalty. We do not walk like rice farmers.”

Without looking up, Nori sensed her grandmother move to where she stood bent over the chair.

“Discipline is essential. You must learn this.”

She felt a hand pull up the back of her kimono and shift so that she stood exposed in nothing but a pair of thin cotton panties. She shut her eyes.

Her grandmother’s voice went very low. “You are a cursed, wretched thing.”

The first blow with the spoon landed with shocking swiftness. It was the sound, loud and sharp, that startled her more so than the pain. Nori’s teeth came down on her bottom lip, and she felt the skin tear.

The second and third blows were harder than the first. There was no body fat on Nori’s spritely frame to dull the force of the impact. As she always did, she began to count the blows. Four. Five. Six.

She felt a deep ache begin in her back, thumping away in a rhythm she swore she could hear. Her shoulder blades began to shake with the effort of staying upright. Seven. Eight. Nine.

It was hopeless now to fight the tears. She allowed them to come with as much pride as she could muster. But she drew the line at whimpering. Even if she had to chew a hole through her lip, she refused to utter a single sound. Ten. Eleven. Twelve.

Over the roaring in her ears, Nori could hear her grandmother begin to pant with the effort of such physical exertion. Thirteen. Fourteen.

That was enough, it seemed. For a moment, both of them stayed in their assumed positions. No one moved. The only sound was her grandmother’s slow, ragged breathing.

Nori did not need to turn around to know what happened next. She was not sure if she was witnessing the events as they unfolded or simply seeing them in her mind’s eye. Her grandmother slowly lowered her arm, taking care to readjust her clothing. Then there would come a look: stern, slightly apologetic. Perhaps there was even some pity there. But then the look would shift into polite indifference. Yuko’s thought process had already moved on. It was not until Nori heard the creaking sound of her grandmother descending the steps that she allowed herself to stand up.

And now the third act of the play commenced.

The stitch in her side reacted violently to the change in position, and Nori twitched as if something had stung her. Inhale. Exhale.

She raised a hand to her face and wiped unceremoniously back and forth. In about an hour or so, Akiko would come up with a warm towel for her bottom. Until then, it was best to avoid sitting. The welts on her buttocks and upper thighs would disappear in a few days. Now that she was alone, the pain in her extremities made itself fully known. As if resentful at being left out of the mix, her stomach began to clench and release. But she kept her chin high and made no sound.

Nori didn’t even know for whom she was performing at this point.

Sometimes she thought it was for the invisible eyes that she swore her grandmother had transplanted into the walls. Other times she thought it was for God. She had a theory that if God saw how brave she was, even when she was alone, He would grant her some kind of miracle.

Gingerly, she stepped out of her kimono so that she stood in nothing but her cotton slip. Though she knew she shouldn’t, she left it on the floor. Akiko would see to it. As far as Nori knew, Akiko was not one to report back on all of her doings—for surely, if that were the case, Nori would receive a great many more beatings than she did.

She liked to believe that Akiko did not hate the task to which she had been assigned. Though it was insulting work to be assigned to tend the family’s bastard child, at least it did not take much effort. Nori tried to make it easy on the poor woman, as much out of guilt as out of ob

edience.

She inched, so slowly that she began to feel comical, over to the prayer altar on the opposite side of the room. Though one of her assignments was to pray thrice daily, Nori did not mind. In fact, she rather liked it.

The altar was by far her favorite possession, though it was arguably not even hers. It was yet another cast-off possession of her mother’s. It was nothing special—just a wooden table with a cloth of royal purple velvet spread across it. The edges of the cloth were trimmed with gold thread. An intricately crafted silver crucifix sat atop it, with two candles on either side. Nori struck a match and lit them both before kneeling on the small cushion she had placed on the floor.

They bathed her in comforting warmth and she allowed her eyes to drift shut.

Dear God,

I’m sorry for my impertinence. I will make sure to ask Saotome-sensei what “impertinence” means so that I can make sure not to do it again. I’m sorry for my hair. I’m sorry for my skin. I’m sorry for the trouble I cause others. I hope you are not too angry with me?

Please look after my mother. I am quite sure she must be very upset that she cannot pick me up just yet.

Please help me to be ready soon.

Amen,

Nori

As she often did when she had finished her prayers, Nori paused. Her favorite thing about God was that He was the one person she was allowed to ask questions. In fact, this privilege delighted her so much that she hardly even minded that nobody answered her.

Fifty Words for Rain

Fifty Words for Rain